Vulnerability Data

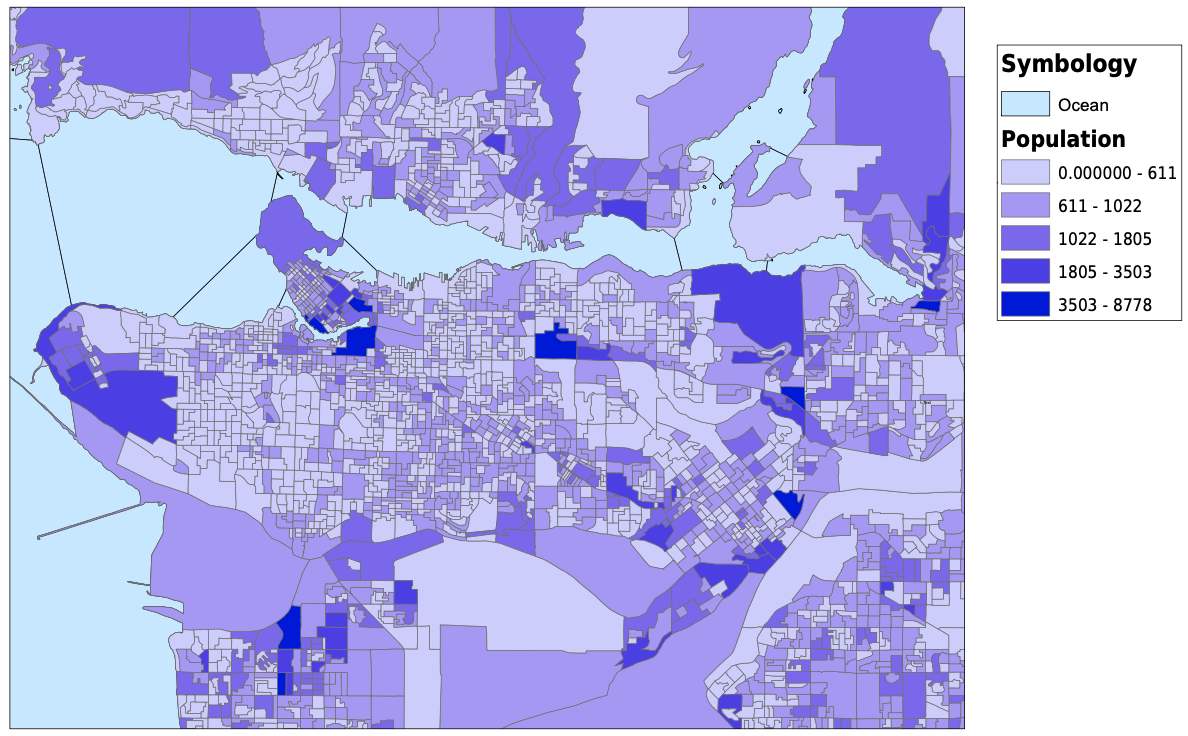

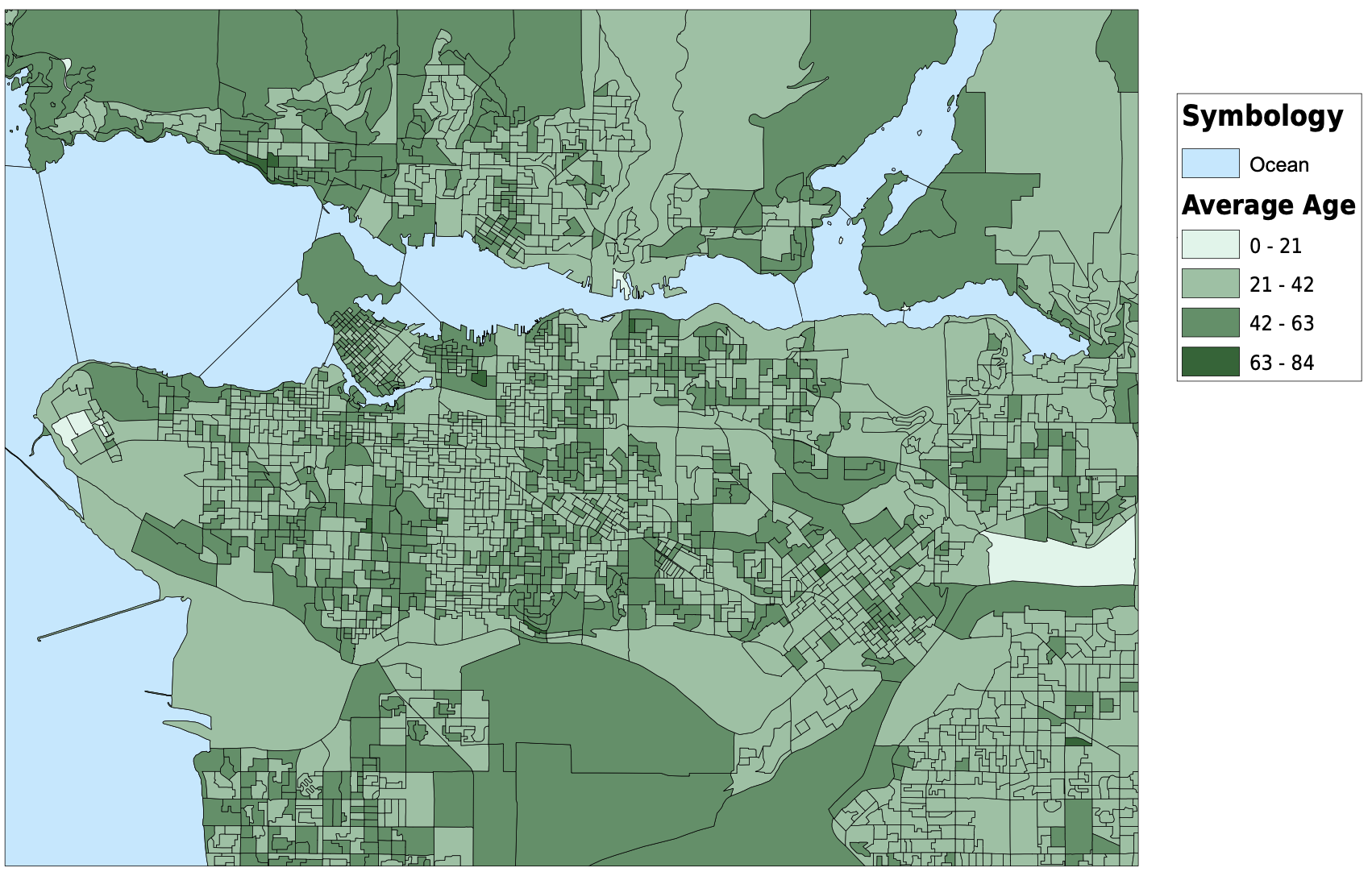

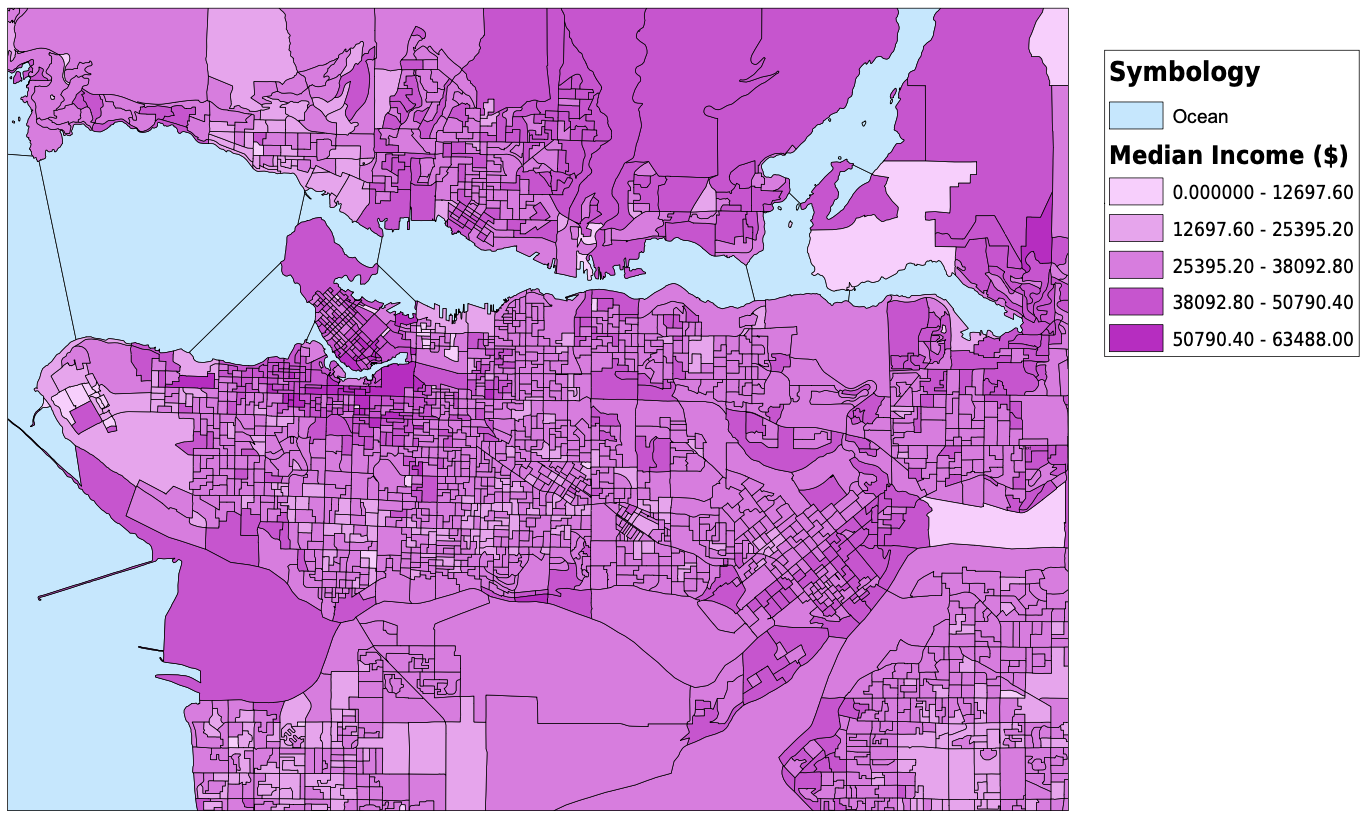

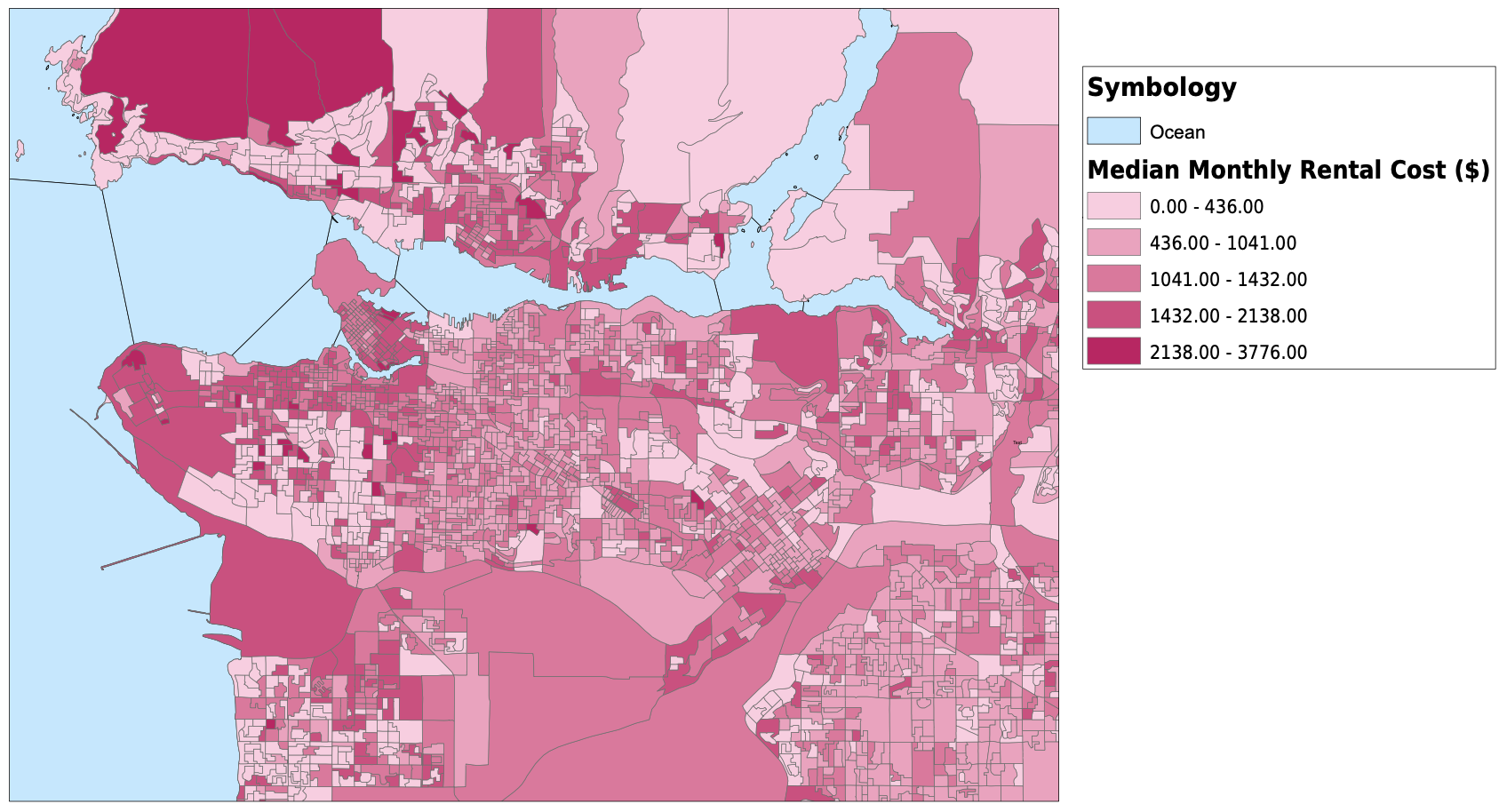

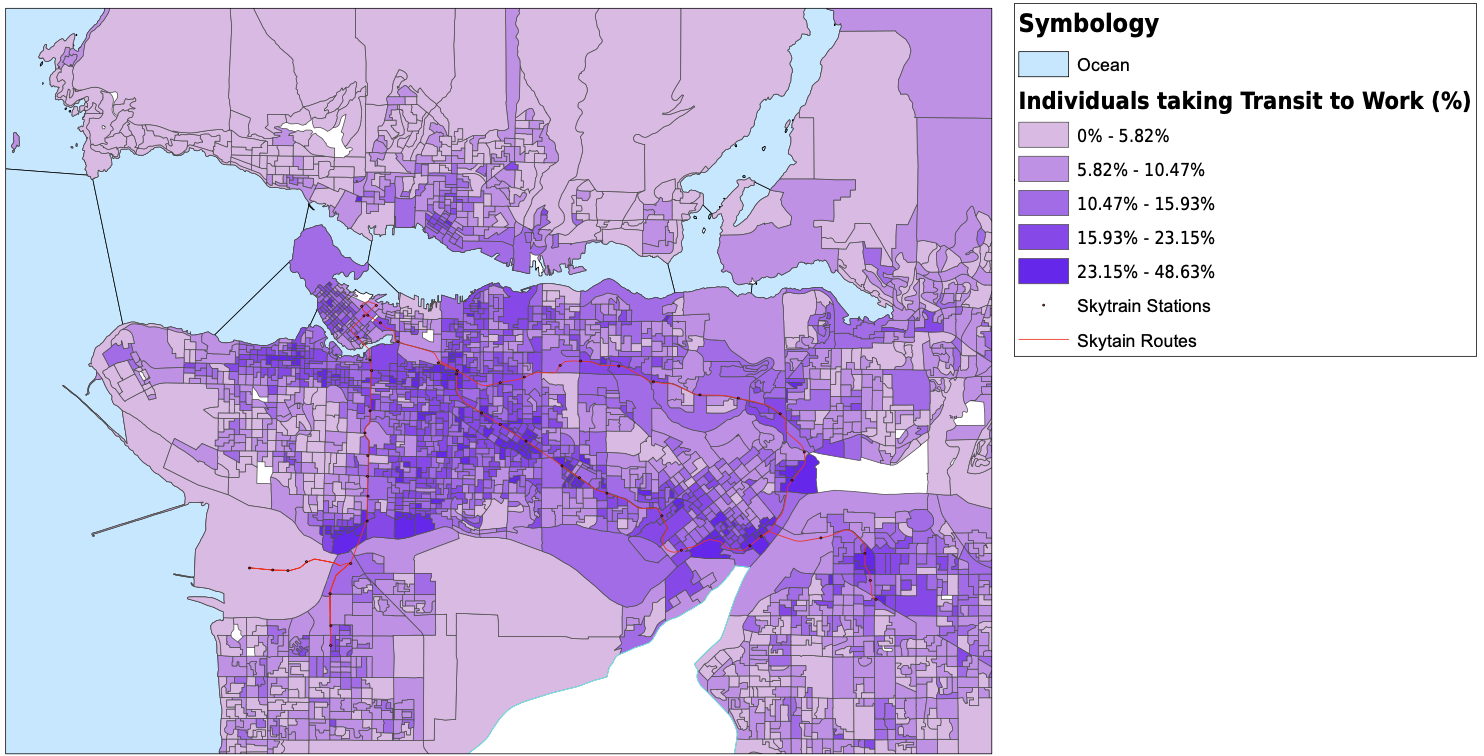

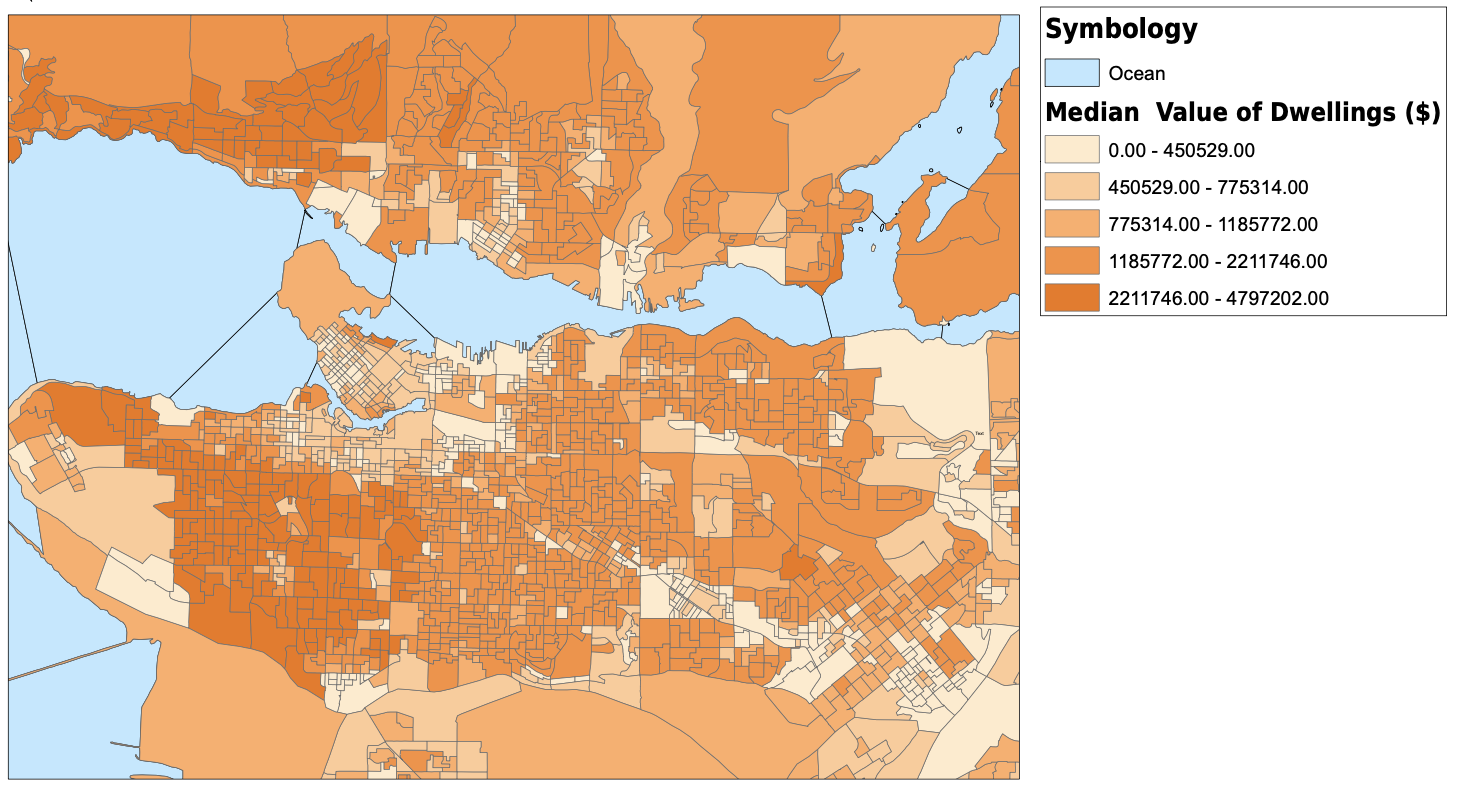

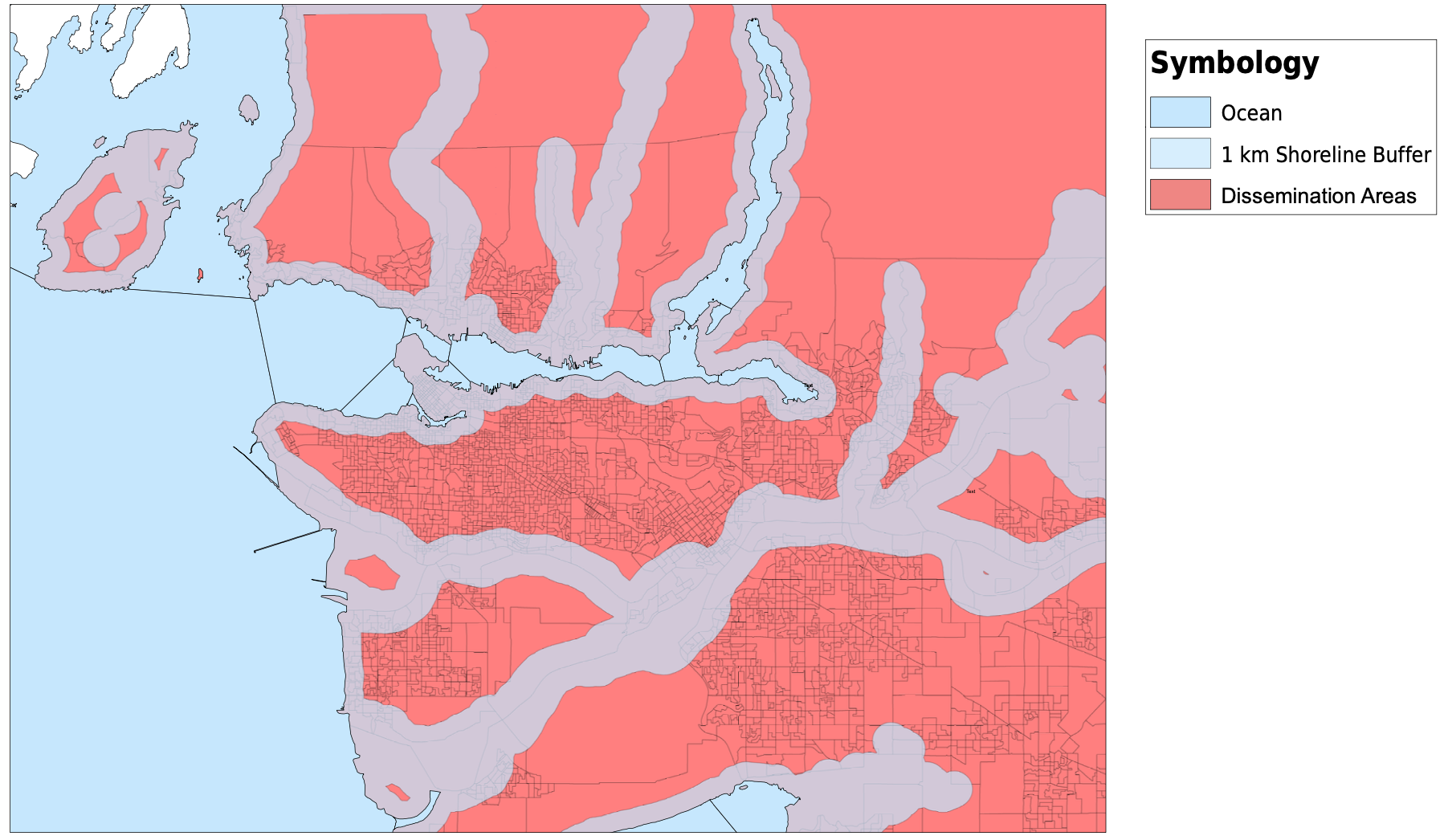

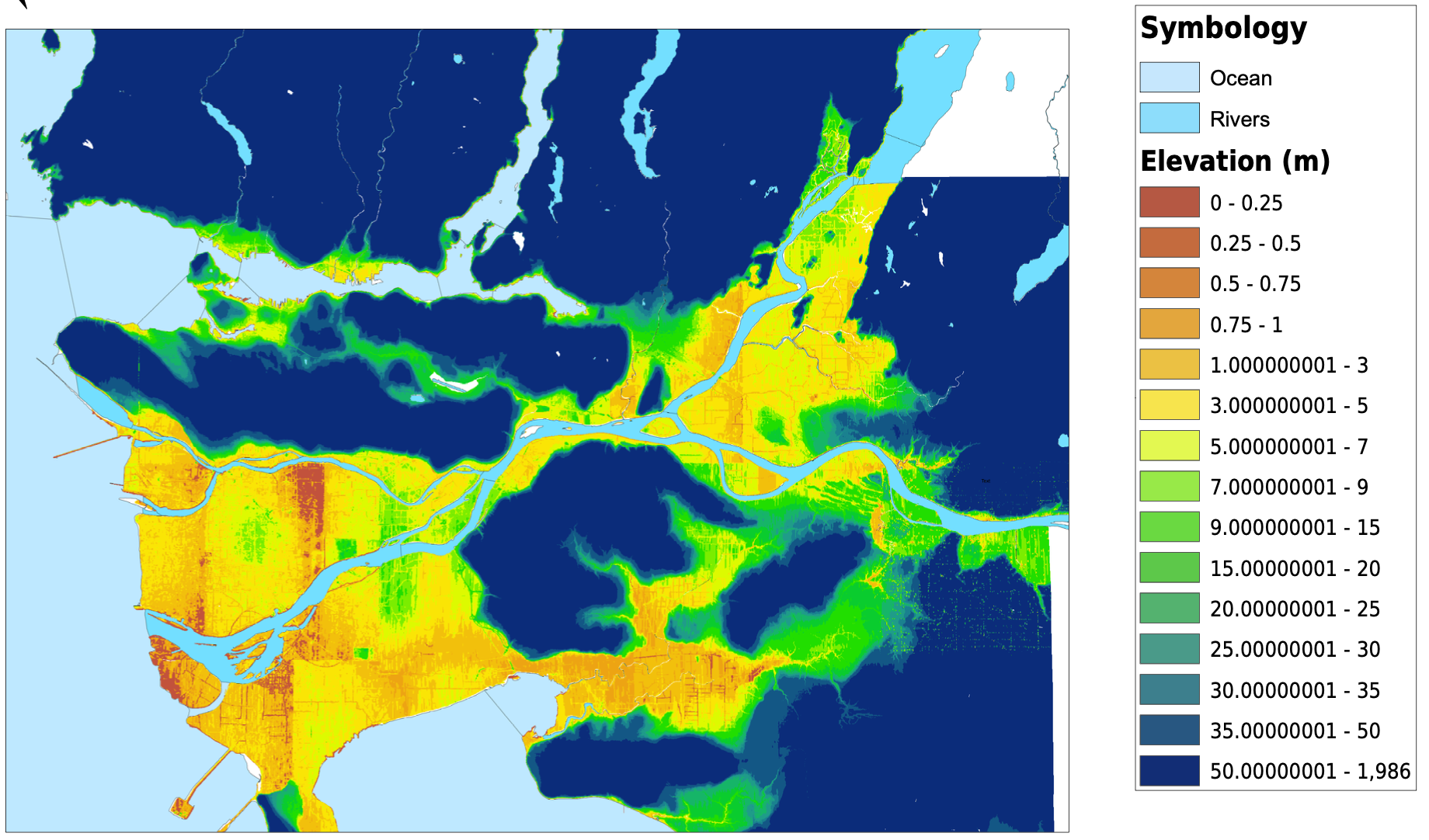

I started my project by downloading dissemination areas from the UBC Library's resource for the Census of Canada, cropped them to the Greater Vancouver Area, and created a new layer for dissemination areas. I altered the data frame's projection to be NAD 1983 UTM Zone 10. The next thing that I did was download tabular data for population, average age, median income, median monthly cost of rent, number of commuters that usually take transit to work, and the median value of dwellings from the University of Toronto’s Computing in the Humanities and Social Sciences website. Once I had all of the tabular data that I needed, I created spatial joins between the dissemination areas and the tabular data, and exported them into new layers. For the transit riders data, I needed to create a new field for transit density, and using the field calculator, divided the transit riders by the total population. After this, I altered the symbology for each layer and had all of my spatial vulnerability data complete and ready to be used. I also downloaded skytrain routes and stations as KML files and converted them into shapefiles. They are plotted with the transit density below. My original plan was to create a vulnerability index that I could compare against elevation or shoreline and have all of the census variables combined into one. In the end I chose not to do this, as it would require me to make too many assumptions and I do not have the knowledge or expertise to make those decisions. For example, in order to create a vulnerability index, I would need to know if a higher age puts you more at risk than a low income. I am not sure how to answer those many questions that were arising so I decided to look at some of the different factors to vulnerability individually. For my analysis, I focused on median income and median monthly rent. I would have loved to analyze the relationship between elevation and every variable that I mentioned above, but it would have been much too timely. Below, you can see all of the variables that I have been looking at, joined to dissemination areas. With a click, the pdf of the map will open.